When We Remember Who We Are

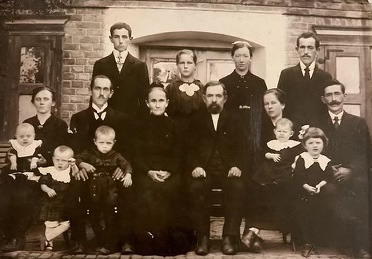

To remember who we are taps us into our strengths. My gaze has often been drawn to this Klassen family photo taken in September 1925 since I became aware of it several years ago. My focus is captivated by my grandparents, Elizabeth (Liese) Friesen and Johann Klassen, in the back row, right side, and even further by my grandmother. February was the month she was born. It was the month that she and Johann arrived in Canada in 1926, and it was the month two years later that Johann died. My eyes see her red hair shining through the sepia tones, a testament to her energy, strength, and courage.

Almost a century after the above photo was taken, she emboldens me. Gathering stories to understand how Mennonites settlers on Namaka Farm in southern Alberta in the 1920s and 1930s adapted to their new surroundings has put me in touch with her in an even deeper touching and meaningful way.

Dad, known then as Bennie Klassen, passed on many of the family stories beginning with his arrival there in March 1930. That was when Liese, referred to in records as “the widow Klassen,” married Peter Jansen at the headquarters of Namaka Farm 2. In a tradition the thirty-six families of German-speaking Russian Mennonites who lived on the settlement brought with them, bride and groom were placed in chairs, then hoisted in the air by celebrants. All almost-four-year-old Bennie remembered was that he “cried his eyes out,” terrified by what they were doing to his mother.

Liese’s Early Years

I imagine the photo marks one of the most auspicious, yet poignant, times of her life. Born into a poor, landless, family in the Molotschna Colony in imperial Russia, she had always had to work hard. Her schooling ended after six years. Seeking a solution to their overcrowding, the Molotschna colony had purchased land from Russian nobles and established the Terek colony in Caucasus in 1901. Landless families like hers received 108 acres each. Seeking a different future, her family undertook the more than 1,000 km arduous migration.

Existence in Terek was fraught with challenges. Oil was discovered in their water and soil. Nogays, Tatars, and Kumeks, who had been displaced from their traditional land, carried out frequent raids. The settlers lived here through the travails of WWI and the Russian Revolution, but danger from the raiders became too great. In a dramatic overnight exodus in February 1918, they formed a two-mile caravan of wagons, animals, and meagre possessions. As attacks and killings intensified, they discarded livestock, implements, and furniture, taking only what they could carry.1 Liese and her family returned to Elisabethal where she and Johann met, fell in love, and married. In the photo, they had been together for five years, were expecting a child, my dad, and were about to leave for a new start in Canada—a land of hope, freedom, and peace.

At the same time their hearts were torn apart. Within the past four months they had buried their two-year-old and eight-month-old daughters who had died from a communicable childhood illness. Johann and Liese were the only ones in that photo who made the difficult choice to emigrate.

New Horizons

After years of revolution, civil war, terror, famine, epidemics, and hyperinflation, the social and political horizon looked brighter. Yet, many, including Liese and Johann, were skeptical enough to leave. Like many in Liese’s family, the other Klassens in the photo chose to stay. The Klassen family had a productive farm in what had become Ukraine, which promised to provide well for them and future generations—until under Stalin’s rule, their barn was confiscated, then their land, and they became impoverished. Extended family members were imprisoned and executed. Survivors were eventually exiled to Kazakhstan. But when the photo was taken, none of this had come to pass and the future appeared optimistic.

Liese and Johann set sail in November 1925, only to be delayed in Southampton, England, for three months to treat Johann’s trachoma (communicable eye disease). All the time, her pregnancy was progressing. By the time they arrived in Swalwell, southern Alberta, after what could not have been a comfortable passage by ship and rail, she was two months shy of her due date. She remained in Swalwell for two months, while Johann went ahead to Beaverlodge, in northern Alberta, joining other Mennonite families who had arrived the previous fall. Here he would proceed with plans to clear land and build a home for his family until Liese and their newborn son could join him.

Legal correspondence referencing the vendors from whom land in Beaverlodge had been “purchased”, indicates that “all the horses, cows, pigs, poultry, and all the farming machinery, seed for the past year, and feed for all their stock and an advance of several hundred dollars for living expenses was made to the purchasers, who went into possession and have broken up some new land and raised a crop, half of which goes to the Vendors, and half is retained for the purchasers’ living expenses.”

Grief and Safe Landing

Johann was likely malnourished from their final years in the U.S.S.R., illness during transit, and the living conditions on what was then a frontier. In February 1928, he succumbed to tuberculosis after fighting it for four months. To make ends meet, Liese took in laundry from workers extending the rail line. With no heat or running water, her work must have been beyond grueling. Widowed with a toddler and unable to speak English, she did what she had to do. The land agreement ended up in a legal dispute and those she trusted, betrayed her. Bereft and destitute, she and Bennie left in late summer to take up a housekeeping position 800 km south. Here she landed safely with a German-speaking family with up to twenty children. They lived on an established prairie farm, where the man of the house adored Bennie.

Starting Again

Two years later, Liese and thirty-year-old Peter Jansen, who by then lived on Namaka Farm, another eighty kilometers south, had met, married, and Dad was crying at their wedding. Mystery shrouded Peter’s background. Legend has it that he had appeared on horseback, riding like the wind across the prairies. He was hoping to settle on Namaka Farm where an aunt and her family were already farming. Research has added missing detail to this story but the legend stands, albeit supplemented by historical records.

Peter had grown up in Berdyansk with at least nine siblings in a prosperous family who operated a mill. For unknown reasons, he became estranged from them and left home at age seventeen, and at some point, joined the Cossacks. That adventure came to a quick end when a ricocheted bullet hit his shoulder, evicting him from their ranks. He spent three years as a P.O.W. in Bulgaria, changed the spelling of his name from Jantzen to make it appear less German, and immigrated to Canada from Hamburg, Germany in 1925, alone. Like Johann, all his family remained in the U.S.S.R.

Namaka Farm

Dad had good reason to cry. Life for him and Liese would continue to be difficult. I can never understand what experiences shaped Peter and cannot judge. He loved to ride horses, loved to engage socially, and by all accounts was well liked by others in the Mennonite community. However, he was not an experienced farmer, nor was he a good provider, even in the absence of the dust bowl and depression of the 1930s. He refused to learn English, saying he already knew five languages and was not about to learn another. It resulted in no end of embarrassment to his children.

The Jansens were not alone when they, like other families, abandoned their farm and moved to Ontario in 1937. Here Peter and Liese worked as a farm labourers and he moved the family often (Dad moved three times in Grade Eight). Peter died in a car accident in 1945 after refusing advice to have his brakes repaired.

Another Restart

Liese never remarried and lived a humble and modest life until she was ninety-three. More loss, hardship, and heartache would visit. She surrounded herself with family and drew great comfort from her church community. At age seventy, she got her first regular, fulltime job, working as a housekeeper in the Mennonite independent living residences and long-term care home where she lived.

Liese never liked the red hair I inherited from her, saying it was a sign of the devil. Yet, until the day she died, she coloured her few remaining strands a definite red, although she called it auburn. I look at the sepia tones in the Klassen family photo and imagine the crown of flaming red hair they mute. Far from marking her as a witch, they illustrate the fiery spirit and strength she drew from for her entire life. Even clouded by tragedy, that point in time marked the beginning of two years which may have been the brightest in her life.

Revisiting her life has reminded me of the strengths I carry, passed on by an outstanding woman. When I’m faced with what at first seem like difficult situations or choices, my mind wanders back to that photo. I recall my grandmother and what, by her example, she has taught me. It’s a quick course correction when we remember who we are. Thank you Liese!

Footnotes:

- “Terek Mennonite Settlement (Republic of Dagestan, Russia) – GAMEO,” accessed January 29, 2024, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Terek_Mennonite_Settlement_(Republic_of_Dagestan,_Russia).

- W.R. Dick to Serjeant Esq., “Canadian Pacific Railway; Papers Re Colonization, Land, and Natural Resources in Western Canada, 1886-1958,” December 21, 1926, M2269, Box 113, ff1047, Glenbow Museum & Archives.

Outstanding article, my grandfather emigrated to the USA early in the century, where my dad was born in Verona PA. They returned to Fiume ,then Italian and opened a restaurant that thrived until the communists took over and closed all private businesses. Then dad mom my brother and me left and lived in a refugee camp in Italy 4 years before landing in Canada where they lived in peace . ( have you sent this article to the the peace convoy people, they have it so tough )

Regards

Bruno

Thanks Bruno. You’ve got quite a family story! Thanks for sharing it. It’s important to keep our history alive, not only so we remember who we are, but also that we maintain perspective!

Liz

Your articles fascinate me with their descriptions of arduous journeys and personal hardships… they also remind me that many of us have ancestors who undertook similar journeys… from where they had family to places where they would need to start over. It’s humbling.. but also encouraging in a way.

Thank you Liz ️

Thank you Bev. Easy to get lost in our own world without considering others or our own histories. Definitely humbling and encouraging.

I admire your efforts Liz, to track down your family history and discover the similarities, struggles, differences as well as achievements passed on to future generations. It makes me wonder a bit of my own family but not enough to invest the time and effort you are putting in. Thank you for this history and your strength to proceed.

all the best

camilla

You’re welcome Camilla! We’re shaped by the lives and stories of our ancestors, so for me, it’s intriguing to find out what I can about them; about me. Thank you!

A hard story, but beautifully crafted. Thank you Liz.

Thank you Carolyn! I love the stories you’re collecting about your families. I know it means a lot to you, and wonderful for your family to remember also.

Beautifully written Liz. My grandparents came to the US in search of a better life. We are fortunate to know their stories

Thanks Pam. We absolutely are fortunate enough to know their stories, which teach us so much. That’s why they’re important to preserve. We can never put ourselves in their shoes, but your grandparents would also have had to make tough decisions, multiple times, and demonstrated much courage and fortitude. There is wisdom in those roots!